Writing Lesson Week One: Cumulative and De-cumulative Story Structure

Hello! Welcome! I'm so glad you’re here! I want you to know upfront that even though I am a published author, writing is not my natural form of expression. I have taken many writing courses hoping to easily piece together concepts swirling around in my mind so that I could write books to illustrate. I have been less than happy with what seems like an ocean of prose and no lifeboats. I've noticed the artistry of writing becomes so important that the story, or the book as a form, is forgotten. The writing courses haven't been that helpful, even though well intentioned. I know I have been guilty of putting artistry over function in my illustrations, but we don't need to talk about that. :) So, I've created this course to share what I've found that brings cohesion to ideas and expression in a delightful way.

I hope this course inspires you and creates a supportive structure for you to get your ideas into book form. I've put together a collection of books that I think are exceptional. These books are the best of the best so keep that in mind as we review writing examples from each week’s theme. I’ll include a book list at the end of the lesson—I hope you find these books inspiring.

I want to ask that you please don't share the course content. I worked hard to put this together and I've tried to keep the price very accessible so anyone can take this course. Thank you!

This week includes:

• How I make a dummy or a working prototype of the book.

• Examples of cumulative / de-cumulative story structure.

• Your assignment

The Book Dummy

Once I have an idea of some characters and some actions that will take place in the book, I like to move to a book dummy because as, you turn through the pages, it's obvious what is working and what is not. Each time you turn through a dummy, little changes become obvious and each pass-through tightens up the story. My heart does a little dance when the book is working and throws little jabs at me when it's not. (Tip: read to the age-appropriate audience for insight on what's working and what is not—it's amazing the clarity that comes to you when sitting with a 4-year-old.) I keep reworking my book dummies until they're tight, feel fluent, and don't "jab" at me as I read through them.

The real secret is to get the ideas out of your head and onto paper right when they arrive. Record your ideas in more detail than you think you will need. You should have a place to put your ideas as soon as they come to you. Lately, I have been using one of those storyboarding journals from Moleskine, but here are a few more options for capturing your ideas: (note: Click for download of pdfs and the dummy for the dummy making lesson.) Here are some other ways I get my story out of my head and onto paper. Choose what works for you, but don't rely on your brain to remember the idea. Get it out on paper in whichever form.

1) Picture book layout thumbnail page.

2) 9 page pdf indicating spreads for a 32 page picture book.

3) How I make a dummy. (Click for a detailed description.)

4) I tape pages on the wall as a layout of the whole book and tape my sketches into place.

•orange pages are: front and back cover

•white: endpapers

•green: the book starting page 1 and ending page 32

You can see by looking at books what the general children book sizes tend to be. You'll want to keep in mind how it will fit on a shelf (too small and it gets lost—too big and it doesn't fit) or how it fits in a child's hands. That said, if your idea calls for something unusual—then give it a try and follow your gut.

A 32 page picture book is most common. It used to be that publishers didn’t stray much from this page count, but more and more there are picture books that exceed 100 pages. (note: Added or subtracted pages need to be in multiples of four.) Here are three examples of picture books with longer page counts that are in the market now.

48 pages

104 pages

112 pages

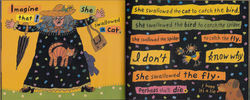

This week we are going to take a close look at cumulative story structure. In a cumulative tale, sometimes also called a chain tale, action or dialogue repeats and builds up in some way as the tale progresses. One satisfying aspect of an cumulative story is that it starts simple and builds upon itself. Often this story structure collapses under the weight of the build-up in a fun or ridiculous finale. These engaging stories make for a great beginning-to-read choices because children can anticipate the progression of the story by the predictability of it's pattern. Here is an exceptional example of the classic There Was An Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly by Simms Taback. Make sure to hover over the image for the descriptions of each page.

There Was an Old Woman That Swallowed a Fly by Simms Tapback, published by Viking 1997. The cover of this book actually has a hole as the lady's mouth. The internal spreads also use a physical die-cut. The left side reveals what the lady just ate; and the die-cut on the right side shows the accumulation of animals in her belly as she goes on to eat the next one. It's a brilliant use of storytelling form. |  The fly's journey before it meets the old lady. This is the title page on the right. If you were counting pages in a picture book, this would be page 1. |  The combination of color, pattern, and collaged photos or prints create a lush feel and eccentric details. |

|---|---|---|

The repetition of "I don't know why she swallowed a ________. Perhaps she'll die" creates a pattern of predictability. |  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  The accumulation of everything the old woman is eating is an escalation in the story, and her character is getting more and more demented with each page turn. |

|  |  |

|  |

Joseph had a Little Overcoat by Simms Taback, the Caldecott winning picture book for the year 2000, is based on a yiddish song Simms loved as a boy. Joesph’s story is about an overcoat getting worn through use and transformed to nothing. I am calling this "de-cumulative" since it keeps the same satisfying structure only in reverse as the cumulative stories.

Simms has illustrated many books using a cumulative story structure: Too Much Noise, There was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly (Seen above), Joseph had a Little Overcoat, and This is the House that Jack Built.

Front and Back Cover: Joesph Had a Little Overcoat by Simms Taback. |  Front-Endpapers |  Dedication and title page. (note: if you are counting pages in a picture book, the title page on the right hand side starts as page 1) |

|---|---|---|

Page 2-3: “Joesph had a little overcoat. It was old and worn. |  Page 4-5: "So he made a jacket and went to the fair” The additional information—“goes to the fair” provides a fuller sense of who Joesph is. The second sentence in the pattern changes for each page spread giving more and more information about Joesph. |  Page 6-7: The cut outs on each page over the jacket (making it into a vest and so on), spotlight the transformation. |

Page 8-9 |  Page 10-11: The repetition brings cohesion to the story and, because it is the same on every page, it also highlights that which changes—the transformation. |  Page 12-13: We get a full sense of Joseph from his actions, expressions, surroundings, and also from others reaction to him. |

Page 14-15 |  Page 16-17 |  Page 18-19 |

Page 20-21 |  Page 22-23 |  Page 24-25: Joesph's material possession—The Overcoat—wears away to nothing but his warm community and connected life grows with each page. |

Page 26-27: There are a total of seven repetitions of the refrain. Ann Whitford Paul of Writing For Children talks about rhythms of seven—as in the days of week, and Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. She says "seven is all around us...It’s familiar and comfortable”. |  Page 28-29 |  Page 30-31 |

Page 32 |  End-endpapers. Simms Taback has created a true gem of a book with masterful die cuts, appealing repetitive structure, nuggets of entertaining surprises, and a delightful example of how our humanity measured by our connection to people—not by our material possessions. |

Here is a description of Simms Taback by a friend of his: "He is always giving. Simms offered more—more interest, more time and attention, more care a bit like a loving mom with a pot of hot soup" —Reynold Ruffins. I think his generosity is reflected in his detailed illustrations of connected community.

Here are a few more examples for our study of this format. I want to broaden the idea of this format to books that increase or decrease in plot turns, humor, characters or objects, and may or may not have the repetition of words. So you can see the variety and effect that either increasing and decreasing these elements can bring to a picture book. Take your time reading the descriptions.

The Mitten by Jan Brett |  INTRODUCING THE CHARACTER: Picture books are so direct that usually the first page of the story introduces the main character. This book has a spread of front matter to describe the Ukrainian origin of the tale. So, story begins on page 4-5 that starts the story. |  SETTING UP THE STORY: The story conflict gets set up right away. This is page 6-7. (You can refer to the downloadable layout page in the dummy section of the lesson.) |

|---|---|---|

PARALLEL SCENES: Brett uses the peep hole shaped as a mitten to give more context to the story. Here we get a glimpse of the next character—Mole. |  The simple base of the story is created—Mole is in the mitten. |  ...and Rabbit squeezes in. |

Add Hedgehog. |  And Owl. |  Badger. |

Fox. |  Bear. |  |

Bear sneezes blowing them all out of the mitten. |  |  Notice all the animals are returning home. |

|  Good Night Gorilla by Peggy Rothman: The perfect bedtime book. |  VISUAL: This book visually increases and decreases. |

|  REPETITION: Good night is the only verbal repeat. |  HUMOR: Again the only word repetition is Good night, but the reader is catching on to the pattern. I still feel a little giggle when reading this book. |

COMPOSITION: Notice the zoo keeper is almost off the page—this placement keeps the focus on the animals. As an illustrator it's an unconventional choice, to only show the backside of the speaking character. But it serves to build up the zoo keep's obliviousness to the animals. |  HUMOR: The humor is building too, as all the animals attentively check on armadillo. |  PARALLEL IN A CHILD'S LIFE: As the zoo keeper / parent says "good night" animals / kids want to stay connected to the zoo keeper / parent. |

HUMOR: Is still building. |  |  REPEAT: Here the zoo keep's wife makes the repeat by saying "good night" to the zoo keeper. |

CLIMAX: The wife's "good night, dear" was broad enough to include so it makes sense that all the animals responded. This is the big reveal moment—and it happens in the dark which makes it even funnier. |  REPONSE TO THE CLIMAX: How simple, direct, and funny is this? |  EXPRESSION: Notice the Gorilla's expression. Also, notice that the eyes are in the exact spot as the previous page for a clear read. |

UNWINDING: Here is the unwinding of the build up. |  HUMOR: But the joke continues and the repeat continues. Rothman didn't have to include this line, but it gives the book more cohesion. |  This time, when the wife says good night the zoo keeper responds. Notice Gorilla and Mouse and the placement of the keys. |

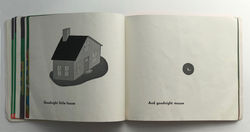

THE FINALE: The last good night is to Gorilla who is already sleeping. This creates a satisfying end after the resolution all the other animals to the zoo. Also, Gorilla and mouse get the prime spot in the middle of the bed. You can look back through the pages and see how Mouse played an important supporting character in this book. And the banana that has been dragged around the entire book has been eaten. |  Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown Illustrated by Clement Hurd |  SUBTLE CUMULATIVE: Brown lists the objects seen in this room, which seem rather ordinary. The combination of the language and illustrations, however, make this an extraordinary book. |

|  SOOTHING: The list has rhythm and rhyme and this is soothing to the reader. Long run-on sentences create a languid, soothing effect. Short sentences create a snappy rhythm. Notice the lines: "And two little kittens And a pair of mittens | And a little toy house And a young mouse" Each line has six syllables except "And a young mouse" has only four. ILLUSTRATION: Notice the brightness of the room and the stillness of the outside night and stars. |  SENTENCE ENDINGS ARE FOCAL POINTS: Notice the sentence endings create the focal point. Example: In "And a quiet old lady who was whispering "hush", hush becomes the focal point of the sentence. If Brown wrote: "Hush" whispered the quiet old lady, the reader wouldn't be left with the thought "hush", the reader would be left with the thought "lady". "And a quiet old lady who was whispering 'hush'" sounds much more lyrical. |

DE-CUMMULATIVE: And now that the list is set, the reader begins the decrease by wishing good night to each object. |  Each item is wished goodnight. |  Notice most of the items on this page and those that those that follow end in soft consonants: balloon, bears, chairs, and on the following pages: kittens, mittens, house, mouse, comb, brush, bowl, mush. The exceptions are clock and socks. ILLUSTRATION: Notice the changing light in the room as it darkens and becomes more sleepy. |

I think the black and white illustrations give a lyrical break between color. |  One by one each listed thing settles down and fades into a still sleep. Here are two words with hard consonants sounds: clocks, socks. They create a small break in the long languid listing. And notice the body gesture of bunny is resisting sleep. Along with turning off lights in the room. |  |

|  |  |

|  ATMOSPHERE: Notice the stillness of the room and the brightness of the moon. The changing light transforms the once active room which is now dark and peaceful and our attention is drawn to the luminous moon and stars in the night sky. |  Ok Go by Carin Berger |

End papers set the scene. |  CUMULATIVE SIMPLICITY: |  WORD AND VISUAL CUMULATION: Here is the baseline. "Go!" |

BUILDS WITH REPEATS: Just the word "Go!" is repeated and additional vehicles are added to the page. |  MORE: Building more repeats of "go" and more vehicles. |  And building... |

CLIMAX |  AND BREAK |  UNWINDING: |

RESET: |  FOLD OUTS: These pages open into a four panel spread. |  Look at this glorious spread. A better way to "go". |

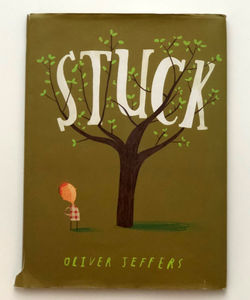

Here are examples of better ways to "go!". |  Stuck by Oliver Jeffers |  It begins rather simply. |

PATTERN: A pattern is being established. |  |  THE PATTERN / HUMOR: That unexpected. |

PREDICITABLE / UNPREDICTABLE PLAY: |  VISUAL: A growing number of "stuck" objects. |  |

|  CLIMAX: This is getting ridiculous! |  A fire truck comes to help—the cliché solution for cats stuck in a tree. We are certain that this is the real solution. Jeffers plays the same gag over and over, but it’s still funny. Floyd throws the fire truck up and it gets... stuck. |

PACING: And then, at a pivotal moment, Floyd has an idea and goes to get a saw. He positions it just so. Jeffers slows the pace by giving this transition more pages. |  REPETITION: Who would expect Jeffers to repeat the same gag? Again, it's still funny! |  It looks like Floyd will cut down the tree…but he instead throw up into the tree. This time, to our surprise and delight,—and to Floyd's delight,—the saw knocks the kite out of the tree. Floyd is happy and forgets about everything else, and flies his kite for the rest of the day...also funny. As he goes to sleep, he thinks he’s forgetting something. |

SURPRISE: Oliver Jeffers uses surprise and the unexpected to delight the reader. The surprises are not shocking or jarring—they are small, funny twists in the story. Sometimes the twist illustrates a different perspective; as how Floyd chooses to use a saw. Sometimes the twist illustrates the unexpected; as in throwing a fire truck into a tree. Sometimes the twist illustrates a joke; as at the end when Loyd felt like he was forgetting something. |  Freedom in Congo Square by Carole Boston Weatherford illustrated by R. Gregory Christie |  This simple, profound picture book recounts a week in a slave’s life in couplets, counting down to Sunday when everyone enjoys a free afternoon in Congo Square. The poem begins and ends with a spread of historical background which provides context for the story. The illustrations are reminiscent of folk art. The countdown begins on Monday. |

CUMULATIVE AND DE-CUMULATIVE AT THE SAME TIME: The days count down to Sunday, creating a de-cumulative structure. The brutality of slavery increases every day creating, however, a cumulative structure of tension / anger / sadness. |  SENTENCE LENGTH: Notice the shorter sentences have more energy behind them than the run on sentence we find in "Good Night Moon". |  |

The story is a poem told in couplets. The couplets count down the days to Sunday, echoing the experience of the slaves as they wait and look forward to that one free afternoon each week in Congo Square. The first half of the book is the count down and the second half is the celebration of being together in Congo Square. |  |  PACING: The pacing slows down here, (with the insertion of three more spreads) assimilating the experience of waiting for Sunday in Congo Square. |

|  CLIMAX: The rejoicing in Congo Square fills the next five spreads of the book, though I only show two here. |  The concise and poetic telling of this story makes this one of my favorites of 2016. |

Sky High by Germano Zullo Illustrated by Albertine |  MATERIAL CUMULATIVE EXTREME: This book begins with two mansions as it's baseline... |  ... and then come the additions. |

The book has a blue-print like quality with the line drawing illustrations and listed of items. The text is a list of the luxury items being added to each mansion; as well as pompous titles for the artists, designers, and engineers involved in it's construction; and descriptions of how spaces will be used. |  BUILDING MORE: |  CLIMAX: The warning: "It is completely impossible to build any higher" |

RESPONSE: Response to the final warning. |  THE OUTCOME: |  IRONY: Lounging on the top floor the owner says, "I want to order a pizza." |

The owner instructs how to deliver the pizza. |  DETAIL OF PREVIOUS PAGE: A description of how to enter the building to deliver the pizza. |  The pizza delivery leaves the pizza on the door step... |

...where the pizza is taken by a wild pig... |  ... and shared with other pigs. |

So—you can see the variety and effect that either increasing, decreasing, or doing both can serve as a supportive structure in a picture book.

Some other things to keep in mind while creating stories:

1) Repetition

2) When to break repetition or when to make the response different.

3) Long, languid sentences—short snappy sentences.

4) Sounds of consonants in your words:

Soft Sounding Consonants: L, M, N, and R

Hard Sounding Consonants: B, C, (when it's a hard C), D, K, P, Q, and T

5) How can your story build / cumulate?

6) How can your story decrease / "de-cumulate"?

7) Does your story have parallel themes of building and decreasing?